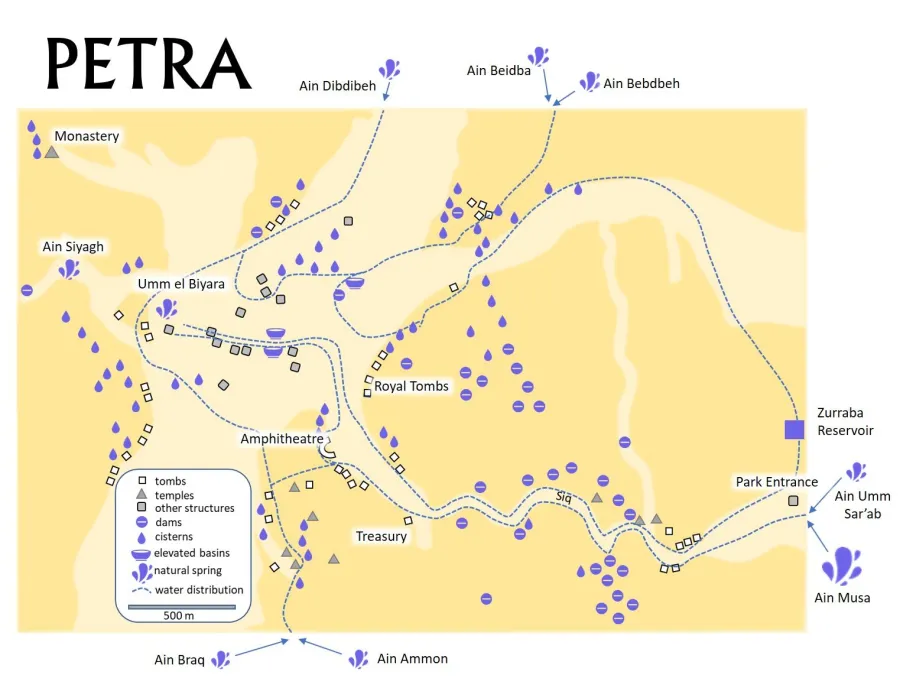

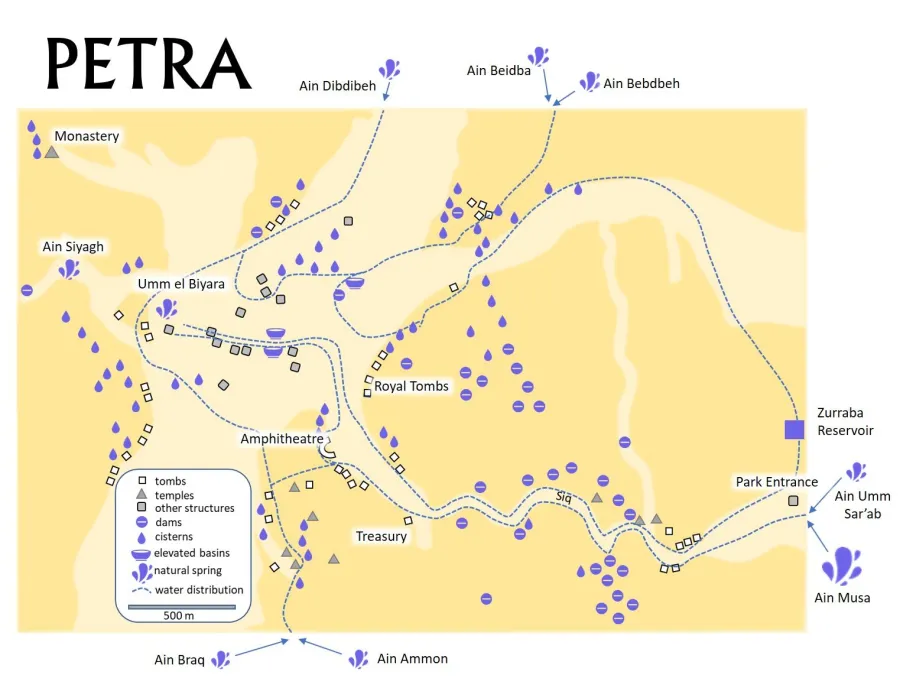

The Nabataeans excelled in surviving the desert by implementing advanced water management techniques. They constructed rock-cut channels and underground water pipes to transport water from permanent springs and seasonal streams. In addition, they developed hidden underground cisterns to collect and store water, protecting it from both evaporation and potential threats. These innovative strategies showcased their mastery of engineering and resourcefulness, allowing them to thrive in arid environments.

The Nabataean city of Petra in southwestern Jordan was built in a desert region, where water was scarce. However, the Nabataeans were able to create an elaborate water supply and distribution system that allowed them to thrive in this arid environment. The system consisted of a network of channels, dams, cisterns, and pipelines that collected and stored rainwater and channeled water from natural springs into the city. The city of Petra, first founded around 312 BC by the Nabataean Empire, was a viable city for close to 1,000 years. The Petra water system needed to be extremely robust to sustain the population for so long. Much research and investigation revealed amazing facts about how the city of Petra thrived in such a dry climate. Although earlier versions of water gathering and distribution systems existed around the Petra area before the Nabataean Empire, The Nabataeans vastly expanded the Petra water system to capture the water sources much more effectively. Water from natural springs and rainwater were efficiently captured and utilized. An intricate and ingenious system of reservoirs, channels, pipelines, dams, cisterns and basins supplied water to a population of some 30,000 continually and consistently throughout each year. Petra’s water requirements would have been roughly 1,800 m3/day (475,000 US gallons/day) based on presumed per capita and public area requirements.

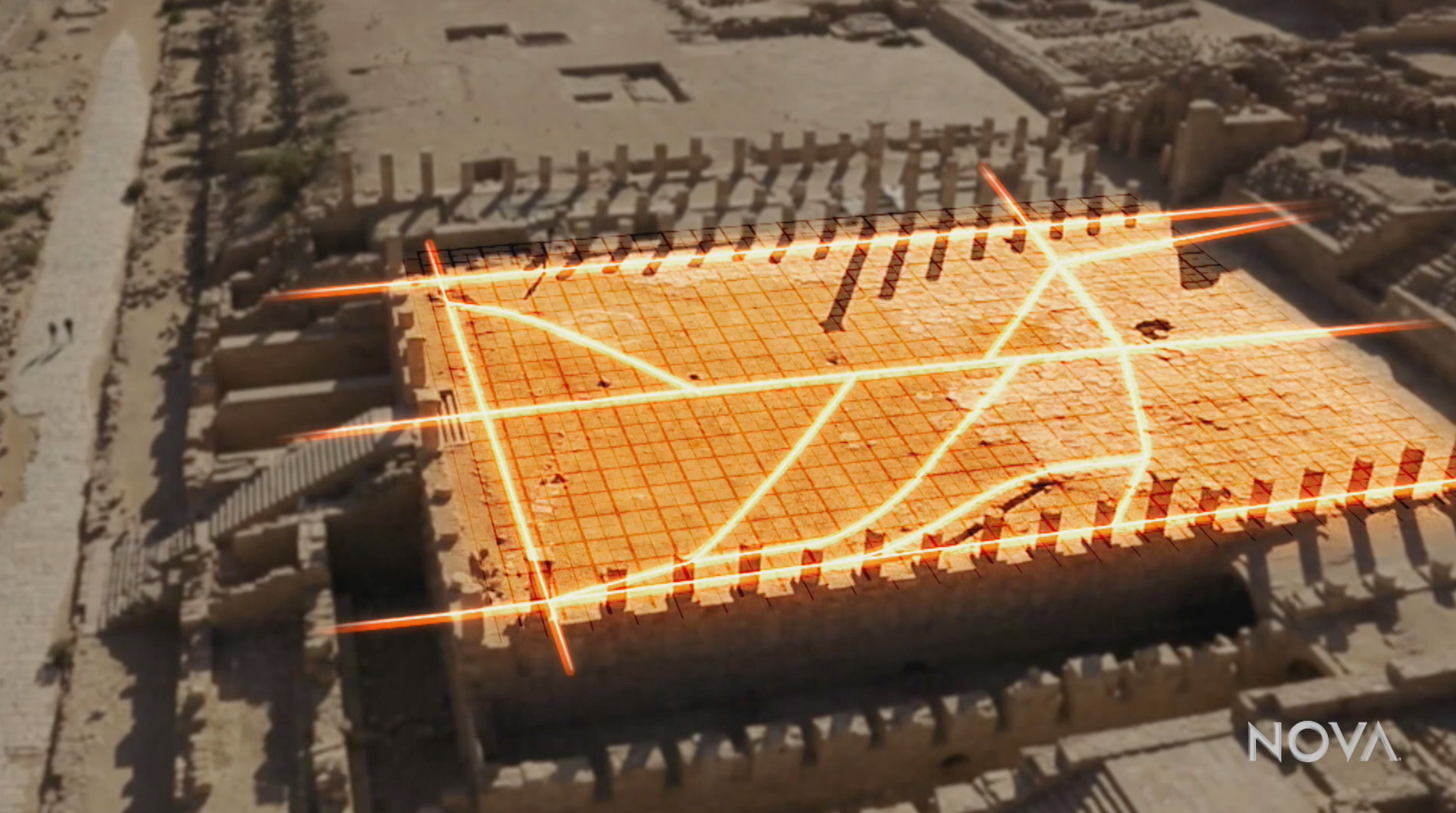

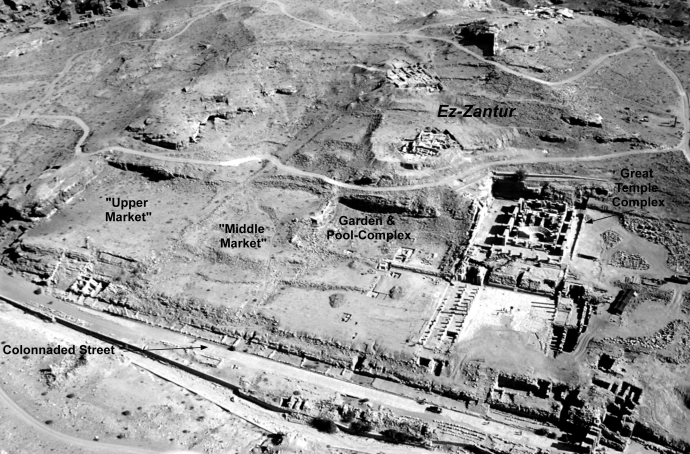

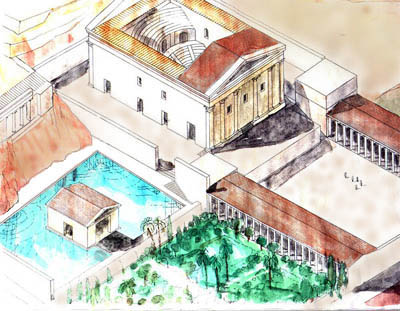

The Petra Garden and Pool Complex in the center of Petra, initially thought to be a market area, has been identified through excavations as an elaborate Nabataean garden with a large swimming pool, island-pavilion, and intricate hydraulic system. This unique structure, the only known example of its kind in Petra and the region, has been a focal point in discussions about the wealth of elites and the display of power through water features. Situated along the main colonnaded street between the Great Temple and the "Middle Market," the complex's location underscores its significance in local civic life. The terraced complex, measuring 65 x 85 meters, likely featured an ornamental garden, bisected by walkways and smaller structures. A large pool, 43 x 23 meters and 2.5 meters deep, with a pavilion at its center, dominated the area. The complex, painted in dark red, orange, and bright blue, would have presented a visually stunning sight with water and exotic vegetation against the backdrop of a 16-meter-high cliff face modified for hydrological purposes. Built during the reign of Nabataean king Aretas IV (9 BCE-40 CE), the complex remained in use during the Roman annexation of Petra in 106 CE. Archaeologists have identified nine distinct phases, including construction, renovation, and eventual abandonment in the late second to third century CE. Damaged by the earthquake of 363 CE, the site was repurposed for agriculture until the mid-20th century. Excavations led by Leigh-Ann Bedal in 1998 revealed the complex's complexity, including hydraulic management, exotic plants, and the large swimming pool. Ongoing research involves the study of botanical remains, shedding light on the historical and cultural significance of the Petra Garden and Pool Complex.

The ceramic pipes used in Petra were typically made from clay or terracotta. These pipes were carefully crafted and assembled to create a network that facilitated the transport of water from sources such as springs or cisterns to various locations within the city. The pipes were often laid underground, preserving the water from evaporation and reducing the risk of contamination. The precise construction and arrangement of these ceramic pipes allowed the Nabataeans to channel water to different areas of Petra, including residential areas, gardens, and likely the Petra Garden and Pool Complex. The system demonstrated a remarkable understanding of hydrodynamics and water management, showcasing the Nabataeans' engineering prowess. The use of ceramic pipes in Petra is a testament to the ingenuity of the Nabataean civilization, enabling them to create a sustainable and efficient water supply system in a region where water scarcity was a significant challenge. The remnants of these ceramic pipes and the overall water management infrastructure contribute to our understanding of Nabataean technological achievements and their ability to thrive in a desert environment.

Major pipelines on the north wall of the Siq featured sediment filtration basins and served specific hydraulic functions. The south-side water channel likely supplied water for animals accompanying people passing through the Siq. The northern wall channel had open basins for personal use, integral to the hydraulic design. The system included surface and underground cisterns, multiple pipelines from various springs, and flood control measures. The city's main water supply originated from the Ain Mousa spring, combined with waters from the Ain Umm Sar’ab spring. A flood bypass tunnel at the Siq entrance, along with an entry dam, reduced flooding. The early Siq water channel was replaced by the Siq pipeline, revealing advanced hydraulic technology. Partial flows in some pipeline sections were observed, potentially allowing for flow observation and cleaning. As the population increased, a north-side pipeline extension provided potable water to further areas of Petra. This extension supplied water to structures in the B-2 district and the Nymphaeum. Additional pipelines extended to the Temple of the Winged Lions and major tombs. Springs both within and outside city limits supplied water through pipelines, feeding reservoirs for various purposes. The Nabataean pipelines, composed of terracotta elements, featured sealed joints with hydraulic cement. The system served cisterns, workshops, and monumental tomb structures. Royal compounds in the terminal pipeline area were supplied by the Wadi Mataha pipeline extension, ensuring abundant water even in drought periods. Multiple pipeline sources allowed for cleaning outages and facilitated water transfer across the city, ultimately discharging into the Wadi Siyagh. The engineering behind the slope of the Wadi Mataha pipeline was a critical consideration for optimizing flow rates.